“Your excellency, the Greeks of Epirus are in desperate straits. There is no security, no equality. They are persecuted, tortured, robbed, beaten and conspired against. Greeks are murdered daily in the street…”

When Giorgos Hatzis wrote this letter of protest to the head of the Ottoman Reform Commission in Epirus, in 1912, the whole of Epirus was still part of the Ottoman Empire.

However, it was a part of the Empire that had been in constant revolutionary turmoil since the beginning of the century. The north of Epirus was steeped in chaos as Albanian bands roamed the countryside, plundering Greek villages and murdering their inhabitants, taking advantage of the lax Ottoman presence in the region. In the southern, more developed regions, security and persecution became tighter and tighter, as enlightened Greek educators and patriots became more vociferous in their demands for the liberation of Epirus and its integration with the kingdom of Greece.

Revolt in Epirus seemed to be a matter of time. The harsh, barren and mountainous terrain of Epirus bred a hardy and independent people, determined to retain their identity. Having the largest percentage of migration in the whole of the Greek world, Greek migrants such as Tositsas, Averof, Zappas and Zosimas, who created great fortunes in Romania, had over the past century, begun to build schools in Epirus, churning out teachers and intellectuals who, influenced by the enlightenment and the rise of nationalism, began openly to conceive Epirus as an integral part of the new Greek state.

Epirus as well had a tradition of resistance and revolution against the Ottomans. Throughout the years of Ottoman rule, the region was perpetually revolting against the conquerors. From the revolts of Kastriotis in the fifteenth century, those of Kladas in the sixteenth, the great revolt of the bishop Dionysios in the seventeenth century which culminated in the expulsion of Greeks from the citadel at Ioannina as well as the resistance of Souli and the revolt of Ali Pasha against the Sultan, Epirus was constantly enmeshed in the throes of revolution.

Secret societies began to be formed, such as the “Epirotic Society” founded by the northern Epirot guerilla leader Spiros Spyromilios in 1908, who lobbied the Greek government to co-ordinate the various Greek rebel movements into a coherent force and train them for revolution. Approximately 15,000 weapons were smuggled into Epirus and distributed by the Society, until an embargo on arms was imposed by the Greek government in 1909, in an effort to improve Graeco-Turkish relations. Almost immediately, the Ottoman government recognized Epirus as primarily an Albanian region and encouraged Albanian and Vlachophone bands to attack Greek villages. Attacks on the villages of Zagoria near Ioannina were especially brutal. During the whole of this time, the Society, cut off from aid by a pliant and weak Greek government, managed to keep the peace, destroying many marauding bands and effectively guarding villages against attack. The contribution of the clergy, especially the bishop of Konitsa, Spyridon who later became a minister o the independent state of Northern Epirus and archbishop of Athens, helped to keep the flame of Hellenism alive during this difficult period, while continuing efforts to reconcile all sides.

Despite this, the Ottoman government, realizing its European empire was crumbling, decided to play one side off the other. Secret plans were discovered, revealing that the Ottomans were preparing to grant autonomy to the Albanians, giving them territory stretching from Kosovo in the north and encompassing the whole of Epirus. Protests ensued all over Epirus and the Greeks and Albanians who had fought together against the Ottomans for centuries finally decided they could not make common cause together, totally divided by their competing national claims.

In the meantime, the first Balkan War broke out on 4 October 1912. The Balkan states of Greece, Montenegro, Serbia and Bulgaria decided to share the European Ottoman Empire between them, driving the Ottomans out of the Balkans. It was secretly decided that Greece should proceed north into Epirus and push on to Monastiri in Macedonia to link up with Serbian forces.

Epirus once again found itself in turmoil. Bands of volunteers spontaneously formed guerrilla groups in northern Epirus, while in the south, the inhabitants of the historic bastion of Greek independence, Souli, began to place large areas of the countryside under their control. Still more volunteers crept south into Greece, to join the Greek army.

Spy units were formed within Ioannina, the capital of Epirus, which effectively reported the movement of Ottoman troops. Esat Pasha, the governor of Epirus realized that the population was fervently espousing independence. Nevertheless, he treated the populace kindly and with respect, never seeking to promote outbursts of persecution or violence, which usually accompanied revolutionary struggles. “My father was a friend of Esat Pasha,” the late Dorothea Tsombou recalled. “He always said Esat was more Greek than Turkish. Educated in Ioannina, a fluent Greek speaker, he genuinely loved the city.”

Esat was also secure in the knowledge that Ioannina, gateway to the north was guarded by 30,000 troops, stationed on the mountain of Bizani, Heavily fortified, it blocked all passage to the north and was deemed an insurmountable obstacle to the Greek army. By contrast, the Greek Epirus division, numbering 8,000 troops and supported by one infantry company was decidedly weak in provisions and weaponry. It was considered that the Greeks could be held up and allowed to waste away at Bizani, slowing the Greek advance into Macedonia.

The Greek army did celebrate early successes. It liberated Arta on 11 October 1912, advancing to Preveza on 21 October. In the meantime, Spyromilios landed at Cheimarra in Northern Epirus and proceeded to liberate the region. Despite fierce Albanian reprisals, Spyromilios managed to retain control of the region and proceed to liberate other areas of northern Epirus.

However, the advance of the Greek army began to slow. On 31 October, Metsovo was taken, with the help of Italian volunteers. Successive Ottoman counterattacks kept the Greeks holed up at Metsovo. In one of these attacks, the famous Greek poet, Lorentzos Mavilis was killed. Similarly, the Greek advance through Paramythia was also halted by a combined Ottoman and Albanian force.

At this crucial stage in the war, threatened with virtual disintegration, the Greek high command, decided on a three pronged all out attack against the formidable defences at Bizani. Throwing all their strength against the mountain, the Greeks were able to dislodge the Ottomans from a few strategic points, with heavy casualties. However, this maneuvre all but destroyed the Greek divisions, as the Turks were able to counterattack with great effectiveness, causing great loss of life. The undisciplined Greek army was forced to retreat in panic. In desperation, the Greek government appealed to the Ottomans for a cease-fire at he council of London. This was denied as the Ottomans by now believed they were winning the war in Epirus and it was only a matter of time before the Greek army in Epirus would disintegrate from exhaustion.

The Greek high command decided to detach two divisions from the Macedonian front, a total of 10,000 men. While this force did much to relieve the beleaguered Greek forces and finally did tip the scale in favour of the Greeks at Bizani, it had far reaching consequences. The delay at Epirus and the weakening of the Macedonian army meant that the Greek advance into Macedonia was delayed and only achieved at great cost. The Serbs bore the brunt of most of the fighting in northern Macedonia alone and were ultimately were forced to advance and take Monastiri before the Greeks arrived there. As a result, this city of 200,000 Greek inhabitants has remained outside of Greece ever since.

In the meantime, Crown Prince Constantine assumed control of operations in Epirus. To the north, the Greek guerillas were occupied in the fight against the Albanians and could not be of any assistance at Bizani. Hostility soon broke out among the High Command. General Sapountzakis, the commander of the Epirus army resented the fact that Prince Constantine had assumed command. He also could not tolerate criticism of his wasteful strategy of throwing men at the best defended strategic points of Bizani. Prince Constantine decided to direct the Greek forces to the west of the mountain, hoping to smash through the weaker Ottoman lines there.

The attack took place on 7 January 1913 and while losses were significant, the Greek forces managed to struggle through the Ottoman lines, in much heavy hand to hand fighting. Having dislodged the Ottomans from part of the mountain, General Sapountzakis ordered yet another attack on Bizani. Again this met with total failure. Prince Constantine then sent a personal letter to Esat Pasha, exhorting him to surrender Ioannina. Believing he was negotiating from a position of strength, Esat Pasha rejected this exhortation outright. In desperation, Prince Constantine urgently requested reinforcements to be drawn from the Macedonian army. Prime Minister Venizelos, striving to push on and take Thessaloniki before the Bulgarians refused.

Instead, Prince Constantine planned a two pronged attack on formidable Bizani, to be preceded by a decoy attack, while troops stationed at Kerkyra would land at Agioi Saranta in Northern Epirus and swoop down behind the Ottoman army, encircling Ioannina and liberating the whole of Epirus. On 19 February, the Greek army began once more3 to bombard the Ottoman positions. This was a feint, designed to draw out and exhaust the Ottomans and was effective. The next day, Greek divisions stormed various Ottoman positions. Ignoring their orders, which were to hold the captured positions and establish camp, two divisions fought their way to the village of Rapsista, on the outskirts of Ioannina and opposite the Ottoman command post. They remained there at night, not realizing that Esat Pasha had already raised a white flag over his post.

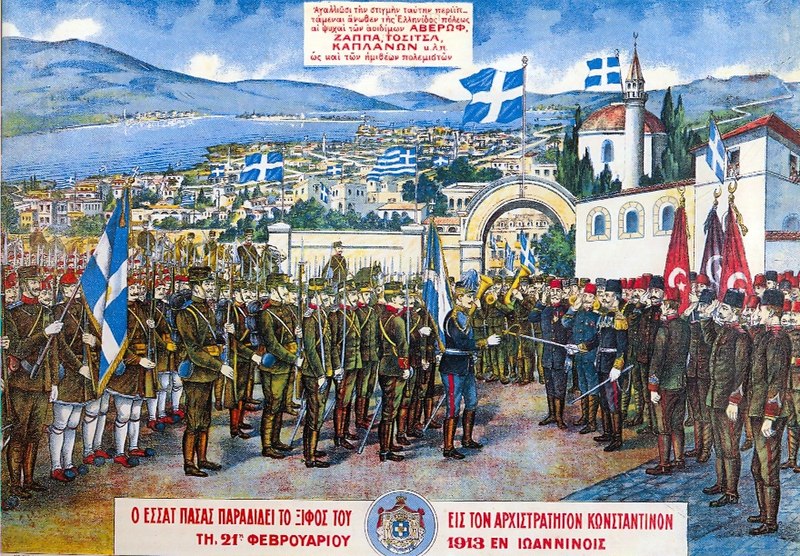

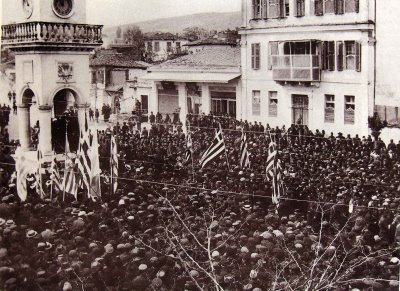

On the next day, 21 February 1913, Esat Pasha called upon Metropolitan Gervasios of Ioannina and informed him that he intended to surrender the city. After several negotiations with Prince Constantine, it was agreed that the entire defending force would be surrendered to the Greeks. At 5:30 am, Greek guns were ordered to stop firing. The next day, the triumphant Greek army entered Ioannina with Prince Constantine, amid frenzied celebrations by the Greek inhabitants.

The late Panagiota Pavlou who was at the nearby village of Perama, remembered: “We had been used to the sounds of bombardment coming from Bizani. The guns suddenly stopped. Moments later, we could hear the sounds of church bells from Ioannina, ringing ceaselessly. Everyone understood. We all poured out of our homes and into the village square, dancing with joy. The men tore their fezzes from their heads and trampled them into the dust. The few Turks that lived in our village were boarded up in their houses and were crying. They knew they would have to leave soon.”

The liberation of Ioannina, the first major success of the Balkan War was celebrated with jubilation in Athens, a welcome relief after the tension felt by the Greek people during the siege at Bizani. However, the war in Epirus was not over yet. Part of the Ottoman garrison refused to surrender and retreated north. Two divisions immediately left in pursuit. On 23 February, Leskoviki was liberated and the Greek army proceeded to liberate the whole of Northern Epirus, entering its capital, Argyrokastro on 3 March.

While the Greek army was readying itself to liberate other areas with significant Greek populations in Albania, Prime Minister Venizelos ordered them to remain behind what became known as the Northern Epirus line, which was to mark the northern limit of Greece’s border, given that Italy declared its intention to oppose Greece by force if it should liberate the port of Avlona.

The liberation of Ioannina and all of Epirus on 21 February 1913 is commemorated with great ceremony in Greece every year. However, Northern Epirus would soon be forcibly detached from the Greek state and become an autonomous nation. After the First World War, its 400,000 Greek inhabitants would be left at the mercy of the newly established state of Albania, to suffer persecution at the hands of the totalitarian communist regime. In any event, the liberation of Epirus marks the apex of Greece’s confidence and success as a Balkan nation and a significant step in the realisation of the Great Idea of liberating the whole Greek world, an ideology which would dominate Greek politics and have far reaching consequences for the nation for the next thirty years.

DEAN KALIMNIOU

kalymnios@hotmail.com

First published in NKEE on Saturday 16 February 2013