VALE THEODORE TSONIS

Men of letters, to use the old expression have traditionally been held in high esteem by our culture. The inference is that it was due to the efforts of these men that our civilization not only endured the mind-numbing and culture destroying years of the Ottoman occupation and that heir efforts to preserve the Greek language and literature provided the impetus required for the liberation and renaissance of Greece into the modern world. Thus, in the Pantheon of national mythology, scholars such as Gennadios Scholarios, Evgenios Voulgaris and Adamantios Korais rub shoulders with more rough and ready warrior types such as Kolokotronis, who by the way, emphasized in a famous speech to the schoolchildren of Nauplion that education and retention of the Greek language were the keys to their county's future, a sentiment echoing the valiant efforts of St Kosmas the Aetolian to bring culture to the masses and arrest their assimilation, a quarter of a century before him.

While in Greece, men of letters seem increasingly to belong to the world of nationalistic schoolbooks of a bygone era, having absolutely nothing to do with the game-boy and Fifty Cent's visit to Athens, they are of particular relevance to the Greek communities of the Antipodes. For in many respects, we are in exactly the same situation as our ancestors centuries before us, save that it is doubtful whether we will be able to arrest the seemingly terminal decline of our mother tongue usage or our increasing ignorance of the intellectual and literary tradition of our culture.

If men (and women) of letters do exist in our community, then surely they are to be classified as those who strive to ameliorate the abovementioned conditions through the promotion of Greek language and literature. They are many such persons and though they are of late increasingly frustrated and ambivalent about the future, they soldier on, guarding the Thermopylae of gnosis against the coming onslaught of barbarism that will inevitably come.

One such particularly noteworthy man of letters was the recently departed Theodore Tsonis whose personage this column has hosted before. He is worthy of mention because he devoted his whole life to the preservation and promotion of Greek literature and did so in a novel way that could only be paralleled with the endeavours of St Kosmas, traversing the whole of Greece in order to preach a Gospel of Christianity and Hellenism. As a bookseller, there were few Greek houses that Theodore Tsonis had not visited. I remember him one day pulling out an old Melway heavily pockmarked with circles, marking all the homes he had visited around Melbourne. "Have a look," he smiled, "there is not a half a page that hasn't received a Greek book over the years."

Tsonis' personal approach to books was fired by a unique understanding of the tradition of knowledge, as something handed down personally from one person to the next, not to be extracted impersonally from outside sources. He was fired with a zeal to lay the foundations for people of diverse walks of life to educate and improve themselves despite any self-perceived lack of qualifications on their part. Thus, instead of attempting to get rid of old stock or pandering to the quick and cheap sales of sub-standard romances of low quality material, he would more often than not be found convincing his customers why they must read a particularly 'useful' or 'important' book, often of lower value than the initial trash they had cast their eyes upon.

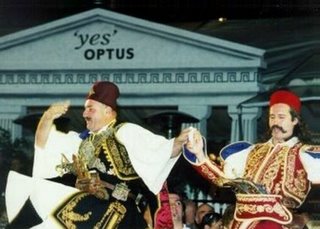

To have a bookseller assume personal responsibility for the quality of the books he purveys is unheard of in our market economy. Yet it is all the more plausible when one considers that Theodore Tsonis' love of Greek literature was so immense that he would take his books to the people, rather than, in the manner of most booksellers, wait for them to come to him. A trademark of the community in his iconic white panel van, he would trawl through the Antipodean streets of Melbourne with a huge smile on his face, books flying off the back seat and into his lap. Lonely, isolated or ill members of the community awaited his visits with great anticipation. A whole generation of migrants entrusted him with the development of their literary aesthetic and he provided them with the spiritual food they so desperately required. A visit to the Greek section of any local library will reveal that most of the books comprising any given collection have originated from him and they have all been lovingly chosen for maximum benefit. Similarly, a visit to almost every single Greek panygyri would reveal Theodore Tsonis and his wife Angela unassumingly purveying the keys to cultural self-preservation, amidst all the sybaritic festivity. Indeed, it was his unassuming and self-deprecatory manner, coupled by a pair of the most piercing and expressive eyes that served to convey his passion as well as his opinion of the most suitable book, to the reader.

Theodore Tsonis was no conservative, bent on retaining an idealized and ultimately time-frozen conception of Greek literary culture, without this having any relevance to our place of temporal transplantation. Instead, he constantly championed the need for the development of local Greek-Australian literature. To achieve this aim, he formed his own publishing entity "Εκδόσεις Τσώνη," which over the years published over one hundred books by members of the community. It was Tsonis' gentle encouragement of writers who were ashamed at their lack of formal education, unsure of their capabilities or the relevance of their message to break the eggshell of self-doubt and emerge triumphant upon the literary scene. Despite the fact that the publication of books in the Greek language in Australia is largely an unprofitable venture, he also single-handedly was responsible for the distribution of these books within the wider community, convinced as he was that the efforts of such writers deserved maximum recognition. He even went to the extent of regularly traveling to Greece to exhibiting Greek-Australian books there as well as organizing the various exhibitions of Greek-Australian books throughout Australia in order to ensure such recognition.

The breadth of Tsonis' vision was not limited to the first generation however. He proved instrumental in encouraging writers of the younger generation to publish their works. In my case, he became my mentor, plying me with books he felt I should read, causing me to compare the works of other Greek-Australian authors and seek the deep psychological reasons that compelled them to write, to criticize my own work and despite my initial reservations, publish it. In doing so, Tsonis wished to inculcate an appreciation and respect for the first generation among the latter generations, as he considered this instrumental if Greek-Australian literature was to have an unbroken and derivative lineage not only from the mother literature but from its founders as well.

Realising, despite his best efforts and with great pain that Greek-language literature in Australia will not enjoy an unlimited sojourn therein, and in order to maintain the link of cultural continuity he felt so passionately about, Tsonis championed the translation of first generation Greek-Australian writers' works into English by second generation writers. In this way, he felt that the communication gap that had given rise to the so-called generation gap could be bridged, this leading to a new level of understanding and ensuring that Greek literature would not, in the coming years be restricted to a Greek-speaking 'elite', but instead would be accessible for all to partake and rejoice in. Under his watchful eyes, several translations of pivotal works, especially in the genre of migrant autobiography were published, to the delight of English speakers who in turning the pages of his publications, found a whole world hitherto only alluded to by their parents, opening up before their very eyes.

Sadly, fate intervened to divert Theodore Tsonis from his work. Instead, it cast him upon another perilous path, that of fighting against a cancer that surreptitiously took hold of him. He applied himself to fighting it with the same gusto he had for life and Greek literature and he slipped away after an intense battle against it for six months, surrounded by those that he loved the most, his wife Angela and his children Antonis and Rita. I remember sitting with him earlier in the year while he told me: "It is imperative that Greek literature survives here. You need to go out and encourage people to write. When the first generation cannot or doesn't want to write, take down the details of their lives and make them known. There are some remarkable stories to be had there. And never forget who you are or what sacrifices have been made for you." When I laughingly remarked that there was plenty of time for that and we are not going anywhere in a hurry, his grip on my arm tightened and his eyes narrowed. Leaning close to my ear he whispered urgently in tones reminiscent of Father Seraphim Rose: "Do it now. It's later than you think."When national poet Kostis Palamas died during the German Occupation, his funeral served as a rallying cry for the Greek people to manifest their resistance against the fascist regime. Another poet, Angelos Sikelianos, moved by how just one man could embody the conscience of an entire people uttered the famous words: "The whole of Greece leans upon this coffin." It could easily be said that not only the Greek-Australian literary community but also the entire Greek-Australian community leans upon the coffin of Theodore Tsonis. For he was more than a fulcrum or a hub in the wheel of community life. He was and still is for that matter, the embodiment of the aspirations and conscience of a people as well as a worthy and sure signpost into the future. Αιωνία του η μνήμη.