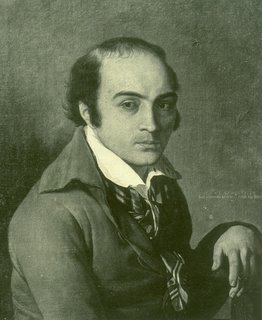

ANDRÉ MARIE CHENIÉR

In his masterpiece of satire “The Devil's Dictionary,” Ambrose Bierce defines poetry as: “A form of expression peculiar to the Land beyond the Magazines.” Be that as it may, the word poetry, whose etymology is derived from the Greek verb ‘to create,’ has played an intrinsic part in Greek culture since at least the days of Homer and Aristotle’s attempts to rationalise and classify it. It is the classical Greek tradition that inspired poetry in the West, though the East has a venerable tradition of its own that may or may not have influenced or inspired Greek poetry in the first place depending on our race’s proximity to the Proto-European Homeland and our own beliefs as to whether such a homeland ever existed, or whether in fact, a some within our community would tell us, we are actually descended from the stars.

Such a poetic tradition serves both as an ancestor and a yardstick to the entire genre, or to use Dylan Thomas’ terminology, “the fundamental creative act using language.” While this means that our venerable progenitors of rhymed and metered verse obtain the recognition they deserve, it also underlines a common underlying perception of Greek civilisation as a whole, that is, that all useful aspects of it were taken by the West from its ancient tradition and that anything occurring after it is of marginal importance. Thus, while we can boast Nobel Prize-winning poets in Seferis and Elytis and a much-translated poet in Cavafy, it cannot be said that Modern Greek poets stand at the forefront of world poetry. Even the few successful poets of Greek background that do exist in the west, by virtue usually of their ethnicity and themes employed, are generally considered of quaint but marginal importance.

This was not always the case however. Enter André Marie Cheniér, who was not only the voice of an entire generation and a prominent poet of the French Revolution but also a precursor of the Romantic movement, doing much to rework the ancient Greek literary tradition and motifs to give them contemporary relevance.

Cheniér was born in Constantinople in 1762, of a French father and a Greek mother, Elisabeth Santi-Lomaca, whose sister was grandmother of Adolphe Thiers, Prime Minister of France. At the age of three, his family returned to France and the young Cheniér was able to steep himself in the literary and social upheavals of the pre-Revolutionary period. Trips to Rome, Pompei and Naples saw him draw inspiration from classical archaism and his Greek heritage. He began his literary career writing idyls and bucolics in direct imitation of Theocritucs Bion and other ancient Greek writers.

All the poems written during his early period such as L'Oaristys, L'Aveugle, La Jeune Malode, Bacchus, Euphrosine and La Jeune Tarentine, expose a fascination with ancient Greek culture. La Jeune Tarentine is especially remarkeable for it being a mosaic of reminiscences of at least a dozen classical poets. However, despite his adulation and emulation of the classical poets, Chénier gives his poems a decidedly decadent, hellenistic feel. The colouring may be that of classical mythology, but the spiritual element is as individual as that of any classical poem by English greats Milton, Keats or Tennyson.

Apart from his idylls and elegies, Chénier also incorprated Greek motifs into his experiments in didactic and philosophic verse in order to fit his universalist vision. When he commenced his Hermes in 1783, his ambition was to condense the Encyclopédie of Diderot into a poem examining man's position in the Universe, first in an isolated state, and then in society. It remains fragmentary. Another fragment entitled L'Invention sums up Chénier's Ars Poetica and his attitude to tradition in the verse “Sur des pensers nouveaux, faisons des vers antiques,” meaning: “Let us express modern thoughts in a form worthy of aniquity.” Orthodox theologian Seraphim Rose would have been proud. Chénier’s vision was so broad that he could even treat biblical subjects, such as his long poem in six cantos, Suzanne in his unique, hellenic manner.

Appointed as secretary to the French ambassador of England in 1787, Chénier was uninspired by Anglo-Saxon culture though he seems to have been interested in the poetic diction of Milton and James Thompson, while a few of his verses were remotely inspired by Shakespeare and Thomas Gray. Assuming the archetypal manner of a Frech stereotype, and in a fashion relevant to the monocultural globalisation of our modern times, he observed: “Ces Anglais. Nation toute à vendre à qui peut la payer. De contrée en contrée allant au monde entier, Offrir sa joie ignoble et son faste grossier.” (The English: A nation anyone could buy if they had enough money to pay for it. They go from region to region throughout the world, offering their wretched joy and coarse consternation.)

The 1789 French Revolution and the startling success of his younger brother, Marie-Joseph, as a political playwright and pamphleteer caused him to refocus upon France. In April 1790 he could stand London no longer, and returned to Paris. The France that he plunged into with such impetuosity was upon the verge of anarchy. A strong constitutionalist and in a manner reminsicent of many of the Social Democrats just after the Russian Revolution, Chénier opposed the radcials, taking the view that the Revolution was already complete with the removal of the absolutist king and that all that remained to be done was the inauguration of the reign of law. Moderate as were his views and disinterested as were his motives, his tactics were passionately and dangerously aggressive. From an idyllist and elegist we find him suddenly transformed into an unsparing master of poetical satire. His prose "Avis au peuple Iran Qais" was followed by the rhetorical "Jeu de paume," a somewhat declamatory moral ode addressed to the painter David.

In the meantime he contributed frequently to the Journal de Paris from November 1791 to July 1792, when he wrote his scorching iambic poem: On the revolt of the Swiss Regiment of Châteauvieux. His devotion to the ancient Greek philosophy of virtue and nothing in excess made him an increasingly outspoken opponent of the new regime and he was forced to flee to Normandy in 1792 in order to escape the September masscres. While his brother entered politics, Chénier's sombre rage against the course of events was manifested by once more employing Greek motifs in his poetry, notably in the line on the “Maenads” who mutilated the king's Swiss Guard, and in the Ode to Charlotte Corday, congratulating France on “slipping deeper into the mud.” Paradoxically enough and proving his versatile and profound learning, Chénier even assisted Malasherbes, King Louis’ counsel, by providing him some arguments for his defence at his trial.

After the king’s execution, he sought a secluded retreat at Versailles and only went out after nightfall. There he wrote various poems including the exquisite Ode à Versailles, one of his freshest, noblest and most varied poems. On 7 March 1794 however, he was arrested while visting a friend by two obscure agents of the Committee of Public Safety (sound familiar?) who were in search of a fleeing marquise.

During the 140 days of his imprisonment in the infamous gaol of Saint Lazaire, Chénier wrote marvellously polemic iambes against the regime of Terror, which were transmitted to his family by a venal gaoler. There he wrote the best known of all his verses, the pathetic Jeune captive, a poem of enchantment and of despair, describing his suffocation in an atmosphere of cruelty and baseness. At sundown on the very day of his condemnation on a bogus charge of conspiracy, André Chénier was guillotined.

Chénier’s legacy was immense. His use of language, though contrived for the modern taste was artful, especially his descriptions of trhe natural world, where he drew so heavily from the Greek tradition. The French critic Sainte-Beuve maintained that Chénier was the first to make modern verses adding: “I do not know in the French language a more exquisite fragment than the three hundred verses of the Bucoliques.” Chénier’s influence can even be felt as Russia, where Pushkin imitated him.

To all intents and purposes, as a poet, a victim of the Terror or even as a Greek, Chénier lies outside the common Greek conscience and this is surprising given our propensity to boasting about our: «καλά παιδιά που προοδεύουν στην ξενιτιά.» Relative obscurity notwithstanding, Chénier is on par with El Greco in so far as he reintroduced elements of Greek culture and aesthetic into a wider discourse in a manner that would not be possible nowadays. Much as the Persians ended up erecting a statue of Themistocles in Magnesia after his death, let us at least be thankful that Chénier continues to inspire French culture, his memory being commemorated in numerous poems, notably the ‘Epilogue’ of Sully Prudhomme, the ‘Stello’ of De Vigny, a statue by Puech and a portrait, for history, especially for us who invented it, has a strange way of repeating itself.

DEAN KALIMNIOU

kalymnios@hotmail.com

Such a poetic tradition serves both as an ancestor and a yardstick to the entire genre, or to use Dylan Thomas’ terminology, “the fundamental creative act using language.” While this means that our venerable progenitors of rhymed and metered verse obtain the recognition they deserve, it also underlines a common underlying perception of Greek civilisation as a whole, that is, that all useful aspects of it were taken by the West from its ancient tradition and that anything occurring after it is of marginal importance. Thus, while we can boast Nobel Prize-winning poets in Seferis and Elytis and a much-translated poet in Cavafy, it cannot be said that Modern Greek poets stand at the forefront of world poetry. Even the few successful poets of Greek background that do exist in the west, by virtue usually of their ethnicity and themes employed, are generally considered of quaint but marginal importance.

This was not always the case however. Enter André Marie Cheniér, who was not only the voice of an entire generation and a prominent poet of the French Revolution but also a precursor of the Romantic movement, doing much to rework the ancient Greek literary tradition and motifs to give them contemporary relevance.

Cheniér was born in Constantinople in 1762, of a French father and a Greek mother, Elisabeth Santi-Lomaca, whose sister was grandmother of Adolphe Thiers, Prime Minister of France. At the age of three, his family returned to France and the young Cheniér was able to steep himself in the literary and social upheavals of the pre-Revolutionary period. Trips to Rome, Pompei and Naples saw him draw inspiration from classical archaism and his Greek heritage. He began his literary career writing idyls and bucolics in direct imitation of Theocritucs Bion and other ancient Greek writers.

All the poems written during his early period such as L'Oaristys, L'Aveugle, La Jeune Malode, Bacchus, Euphrosine and La Jeune Tarentine, expose a fascination with ancient Greek culture. La Jeune Tarentine is especially remarkeable for it being a mosaic of reminiscences of at least a dozen classical poets. However, despite his adulation and emulation of the classical poets, Chénier gives his poems a decidedly decadent, hellenistic feel. The colouring may be that of classical mythology, but the spiritual element is as individual as that of any classical poem by English greats Milton, Keats or Tennyson.

Apart from his idylls and elegies, Chénier also incorprated Greek motifs into his experiments in didactic and philosophic verse in order to fit his universalist vision. When he commenced his Hermes in 1783, his ambition was to condense the Encyclopédie of Diderot into a poem examining man's position in the Universe, first in an isolated state, and then in society. It remains fragmentary. Another fragment entitled L'Invention sums up Chénier's Ars Poetica and his attitude to tradition in the verse “Sur des pensers nouveaux, faisons des vers antiques,” meaning: “Let us express modern thoughts in a form worthy of aniquity.” Orthodox theologian Seraphim Rose would have been proud. Chénier’s vision was so broad that he could even treat biblical subjects, such as his long poem in six cantos, Suzanne in his unique, hellenic manner.

Appointed as secretary to the French ambassador of England in 1787, Chénier was uninspired by Anglo-Saxon culture though he seems to have been interested in the poetic diction of Milton and James Thompson, while a few of his verses were remotely inspired by Shakespeare and Thomas Gray. Assuming the archetypal manner of a Frech stereotype, and in a fashion relevant to the monocultural globalisation of our modern times, he observed: “Ces Anglais. Nation toute à vendre à qui peut la payer. De contrée en contrée allant au monde entier, Offrir sa joie ignoble et son faste grossier.” (The English: A nation anyone could buy if they had enough money to pay for it. They go from region to region throughout the world, offering their wretched joy and coarse consternation.)

The 1789 French Revolution and the startling success of his younger brother, Marie-Joseph, as a political playwright and pamphleteer caused him to refocus upon France. In April 1790 he could stand London no longer, and returned to Paris. The France that he plunged into with such impetuosity was upon the verge of anarchy. A strong constitutionalist and in a manner reminsicent of many of the Social Democrats just after the Russian Revolution, Chénier opposed the radcials, taking the view that the Revolution was already complete with the removal of the absolutist king and that all that remained to be done was the inauguration of the reign of law. Moderate as were his views and disinterested as were his motives, his tactics were passionately and dangerously aggressive. From an idyllist and elegist we find him suddenly transformed into an unsparing master of poetical satire. His prose "Avis au peuple Iran Qais" was followed by the rhetorical "Jeu de paume," a somewhat declamatory moral ode addressed to the painter David.

In the meantime he contributed frequently to the Journal de Paris from November 1791 to July 1792, when he wrote his scorching iambic poem: On the revolt of the Swiss Regiment of Châteauvieux. His devotion to the ancient Greek philosophy of virtue and nothing in excess made him an increasingly outspoken opponent of the new regime and he was forced to flee to Normandy in 1792 in order to escape the September masscres. While his brother entered politics, Chénier's sombre rage against the course of events was manifested by once more employing Greek motifs in his poetry, notably in the line on the “Maenads” who mutilated the king's Swiss Guard, and in the Ode to Charlotte Corday, congratulating France on “slipping deeper into the mud.” Paradoxically enough and proving his versatile and profound learning, Chénier even assisted Malasherbes, King Louis’ counsel, by providing him some arguments for his defence at his trial.

After the king’s execution, he sought a secluded retreat at Versailles and only went out after nightfall. There he wrote various poems including the exquisite Ode à Versailles, one of his freshest, noblest and most varied poems. On 7 March 1794 however, he was arrested while visting a friend by two obscure agents of the Committee of Public Safety (sound familiar?) who were in search of a fleeing marquise.

During the 140 days of his imprisonment in the infamous gaol of Saint Lazaire, Chénier wrote marvellously polemic iambes against the regime of Terror, which were transmitted to his family by a venal gaoler. There he wrote the best known of all his verses, the pathetic Jeune captive, a poem of enchantment and of despair, describing his suffocation in an atmosphere of cruelty and baseness. At sundown on the very day of his condemnation on a bogus charge of conspiracy, André Chénier was guillotined.

Chénier’s legacy was immense. His use of language, though contrived for the modern taste was artful, especially his descriptions of trhe natural world, where he drew so heavily from the Greek tradition. The French critic Sainte-Beuve maintained that Chénier was the first to make modern verses adding: “I do not know in the French language a more exquisite fragment than the three hundred verses of the Bucoliques.” Chénier’s influence can even be felt as Russia, where Pushkin imitated him.

To all intents and purposes, as a poet, a victim of the Terror or even as a Greek, Chénier lies outside the common Greek conscience and this is surprising given our propensity to boasting about our: «καλά παιδιά που προοδεύουν στην ξενιτιά.» Relative obscurity notwithstanding, Chénier is on par with El Greco in so far as he reintroduced elements of Greek culture and aesthetic into a wider discourse in a manner that would not be possible nowadays. Much as the Persians ended up erecting a statue of Themistocles in Magnesia after his death, let us at least be thankful that Chénier continues to inspire French culture, his memory being commemorated in numerous poems, notably the ‘Epilogue’ of Sully Prudhomme, the ‘Stello’ of De Vigny, a statue by Puech and a portrait, for history, especially for us who invented it, has a strange way of repeating itself.

DEAN KALIMNIOU

kalymnios@hotmail.com

First published in NKEE on 3 July 2006

<< Home